You learn to write by writing, and get more confident the more you do it.

A story about storytelling

How we do it at Made by Many, and what it’s done for me

In the last few years storytelling has been quite the thing in business: a fetish commodity which can be bought and sold, a vital new process, and a subject about which textbooks have been written (Stephen Denning’s “The Leader’s Guide to Storytelling” and Carmine Gallo’s “The Storyteller’s Secret”). Yet the term itself remains a bit nebulous and vapour-like, a thing that means different things to different people at different times and in different contexts.

I say that because I’ve been “doing storytelling” at Made by Many for the last couple of years, having in 2015 started work here as an “embedded storyteller”, a title which has been alternately flattering and confusing. In this post I’ll set out how this particular story has developed, along with my views on what storytelling means, how we do it at Made by Many, and something surprising that this job title did for me.

It’s worth starting with the fact that so far this year there’s been a steady and swelling volume of stories being published by Made by Many’s designers, technologists, product managers and strategists. There’s been Sam Small’s series of yarns on the links between personal development and design, and Mike Walker’s exposition of “Product Feels” (don’t get it? Just read the story). We’ve had Peter Parkes’ succinct explanations on Made by Many business processes and Fiona McLaren’s ongoing codifications of the practically undefinable topic of what product managers do. There’ve been stories from developers Sam Murray, Kat Lynch and Jamie Mayes on the intricacies of React Native, AWS Lambda and mobile QA respectively, and we’ve also been publishing opinions, experiences and discoveries: co-founder tim malbon on Digital transformation, CTO Andrew Walker on the similarities between IT acquisition and the film “Moneyball”; strategist Susan Lin’s enlightening exploration on transforming the employee experience; and operations director Matt Williams with a beautifully terse essay on Why We Make. Recently Ilya Poropudas hit the top spot on Hackernews with his sacred cow-slaughtering “What if AI Is A Failed Dream?” story.

On the website there are tons more of these stories which combine the personal with the professional, the factual and the phenomenal – so many that as editor, I can hardly keep up, and it’s worth also saying that’s what I am at Made by Many these days: an editor to this ingenious, tribalistic, often unruly but rarely less than brilliant 35-person micro-society which expresses its opinions, experiences and proficiencies by publishing stories person by person, rather than under the faceless platitudes of “corporate communications” (the recently relaunched website is about as corporate as Made by Many “comms” get).

Our editorial and publishing mechanism works well these days, with specialists writing and, with my assistance, publishing stories on what they do, think and know. Writing and publishing are valuable because they are ways in which individuals and the organisations can learn. Writing may be the most laborious and painful way of figuring out what you actually think about something; but having done it for around 20 years, I can say with certainty that it’s also one of the best.

Nevertheless, it’s taken a certain amount of configuring and reconfiguring to get the operation to this state: Slack channels we’ve opened and archived in the last two years include “blog”, “storytelling”, “content”, “marketing”, “content-marketing”, “marketing-content”, and (woo) “supercharged-storytelling”. None of those endured, and these days we have just one, called “publishing”, because publishing is what matters: writing stories and making them public. Getting them out there in the hunt for attention. A bit of my own background might help to explain why I believe publishing – instead of this vapour-y “storytelling” term – is the important thing.

The Write Stuff

By the time I arrived at Made by Many in 2015 I’d worked in print media as a writer and editor on glossy fashion mags including GQ, The Face and Esquire along with contributing to the Guardian and other newspapers.

(Above: hanging out with Dennis Hopper RIP in Salzburg, a few years ago)

Arriving at Made by Many I knew a little bit about design, and precisely nothing about digital technology or product management.

The learning curve has been steep.

The last print editorial job I had (“chefredakteur”/editor-in-chief of a fashion mag in Berlin) convinced me that I was no good at managing people. Print media has hard deadlines; creative people, such as stylists, photographers and writers, often miss deadlines; and I hated having to bollock people. On the other hand I was quite good at facilitating creativity and self-expression in others, in particular with writing. I did a course at the Institute of Education to put some formal learning around the idea I had of combining editorial practice with coaching and mentoring: basically, helping people find the words (or pictures) to say what they wanted to say.

Two other things seemed obvious to me:

• First, that since it became possible for everyone to publish, the orthodoxy now is that everyone must publish online – otherwise you’re silent and invisible. So, how do you ensure quality?

• And secondly, everyone can write, but what most writers lack is an editor.

I’m not sure Made by Many saw it that way when I started work here, even if it was obvious on arrival that the studio was packed with stories waiting to be told. Last year I helped them tell a few, on the company’s work for the V&A and the World Economic Forum, the problematics of innovation labs, on the multifaceted story of Hackaball, a yarn about technology’s awkward romance with empathy, and so on.

But after a while, it became obvious that this method wasn’t really working, or – mea culpa – I couldn’t make it work. I felt uneasy about writing about things I didn’t really understand; it proved difficult pulling stories out of colleagues for whom client work was, naturally, the priority; and I suffered failures of imagination. Charlotte Hillenbrand, Made by Many’s Director of Learning and Development, and I worked quite hard at retooling this process; things improved, and we started pushing stories through the door. Meanwhile I wrote a thing to help MxM’s specialists write their own stories (don’t take it as gospel, it’s just what, in my mind, can help people who don’t necessarily think of themselves as writers or authors, to make good stories.)

But there was also the fact that I struggled to find an accommodation with this “embedded storyteller” idea. A few friends of mine thought it was a cool job title when I told them about it; others took the piss a bit, remarking that they imagined me as a gnome sitting on a toadstool smoking a hooka pipe, like the Caterpillar in Alice on Wonderland:

Inwardly I reflected that this “storyteller” title sounded somewhat exotic… perhaps a bit Nathan Barley. The tech biz still has a thing for magical realism in job titles, after all. Back in the hard-bitten, cash-strapped, fatally cynical world of print media, nobody would dare adopt such a pretentious moniker.

A question: WTF is “storytelling” anyway?

Well, it isn’t journalism, because journalism aspires to report objective fact, and you can’t do that if the organisation you’re writing about is also the one paying you to do it. Is it the same as content marketing, which communicates brands messages wrapped up in an absorbing editorial package? Or is it “comms”, or just another word for “marketing”? Or is it, in the most simple terms, just talking about what you do, using any medium you fancy?

Incidentally, I’d heard people say that they’d, for instance, “storytold” the results of a workshop to their colleagues. I couldn’t undertsand why they hadn’t just “explained” the results or “talked about” them. So is storytelling some kind of higher-consciousness, web 2.0, power-tool version of explaining? Or is it just writing things down before pressing the Publish button, or speaking them out loud to someone?

I am a stickler for the accurate use of words, and the fabulising of “storytelling” feels suspicious to me. The books I mentioned above provide highly detailed and rational deconstructions of what storytelling can do, in the eyes of their respective authors. Stephen Denning analyses storytelling in the light of leadership, and says that both are “performance arts”. He cites some figures arguing “that persuasion constitutes more than a quarter of the US gross national product” and that if storytelling is “at least half of persuasion, then storytelling amounts to 14 percent of GNP or more than $1trillion” (wow…). Storytelling is big business, apparently, and in chapter after chapter Denning explains how it can be instrumentalised by “leaders”. Meanwhile in a blurb for his book “The Storyteller’s Secret”, Carmine Gallo cites ways in which the usual range of business deities, tech titans and elite TED-talkers (Richard Branson, Elon Musk et al) have used storytelling to inspire the world.

No doubt there’s a lot to learn in these books, but setting aside the fact that only 20 years ago, all of this would just have been called “making a speech about ____” or “writing a book on _____” or simply “saying outspokenly that _____”, none of it really helps to define exactly what is meant by storytelling today, and what it is apart from being a fashionable idea.

Is storytelling about launching movements, as Gallo claims Sheryl Sandberg did with her famed “Lean In” book? Or is it about explaining to colleagues what happened in the meeting this morning? Or is it, as Made by Many’s Alex Harding has convincingly, er… explained, using videos instead of 100-page PDFs to explain things to time-poor clients?

All this is why, earlier this year, I urged Made by Many to vapourise “storytelling” entirely from the internal vernacular, and look elsewhere for meaning and value and ways for the company to talk publically about what it’s good at.

Down the pub

One evening in spring I went for a drink with Made by Many co-founder Tim Malbon and after shouting at each other over several pints of IPA, we figured out a new way: a simpler way. I’d act as editor to Made by Many’s specialists and the stories and blogs they write. It didn’t matter if these specialists weren’t confident or competent in the written word (there’s no reason they should be, since they’re not professional writers; on the other hand, Made by Many has plenty of talented prose stylists and rhetoricians).

Neither would it matter if they might be afraid of or challenged by doing writing, as many people naturally are, as if there is an imaginary schoolteacher hovering behind their left shoulder, ready to descend with an angry green Biro. In writing as in dancing, the only real way to look stupid is by not doing it at all: everything can be fixed in the edit.

Tim and I agreed to attempt a “Story Surge” of publishing 25 piece of content in 50 days. In the end we published 26 stories in 50 days, and we haven’t looked back since.

What editors do

Before I get replaced by AI, there are a few other things about editing and publishing methodology that are worth highlighting here:

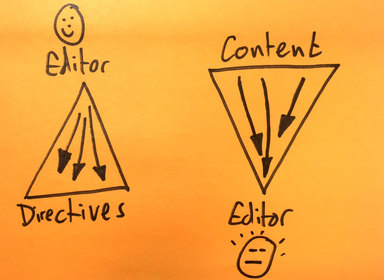

1. If you’ve seen films like “The Devils Wears Prada” or “The September Issue”, it’s easy to imagine that magazine editors are icy, remote figures who sit at the top of a hierarchical triangle, issuing diktats and directives downwards to staff on what’s hot this Fall, or why #VR is The New Black. The reality is that more often than not, it’s an inverted triangle in which every single piece of content that goes into a magazine funnels down through the editor as he or she prepares it for print. The last one I edited had 256 pages per issue, which meant at least one but usually many more pieces of content per page, which all had to be ready at a certain moment in time, edited, colour corrected, proofread, legalled, thought about, and edited again.

This means that:

Good editors facilitate their writers and contributors: understand them, trust them, empower them, collaborate with them, assist them in identifying blind spots and act as proxy readers. Some editors can be “light-touch” to an almost Zenlike degree. That’s certainly been the case with the best editors I’ve worked with as a writer – Alex Bilmes first at GQ and then Esquire, Richard Benson and Johnny Davis at The Face magazine. Some editors may be totalitarian dictators, but the best ones are facilitators. Similarly, coaching assumes the answer is in the client, rather than the coach; I assume the story is in the writer, and it’s our job to bring it out together.

A stream of individual stories coheres into a collective editorial identity; thus the difference between the way a magazine and a digital product studio publish isn’t so big.

Storytelling means whatever the person using the term wants it to mean, and that’s why it’s a complex tool to use. But my feeling is that it has a native, unchanging meaning as well.

I say that because as with “passion”, “empathy” and “vulnerability – three other natively, organically human qualities and behaviours which business has been excited about for a while – storytelling is something that exists and happens among people, in the real world, but which doesn’t quite survive when transposed into the empirical models of business process. Or when it does, it loses much of its power and, for want of a less corny word, its authenticity.

On the other hand, people tell stories to one another all the time without being conscious of “storytelling” – it’s just something we do to get through to others.

Either way, the proof of my intuition that Made by Many was a place packed with stories came one Thursday evening last year, when a knot of colleagues congregated at sundown onto the sofas facing the studio’s big window. The next day was a bank holiday, and everyone was exhausted and relieved. Bottles were opened and a sort of campfire atmosphere emerged, with everyone spinning yarns on work, clients and projects along with the latest news on immersive theatre, views on restaurants worth visiting, feelings about babies on the way, holidays, bikes, gifs, and so on.

That, it seemed to me, was storytelling in the purest and realest sense: so pure and real that everyone had forgotten that the pubs had closed by the time we all left, eager to carry on talking.

Storytelling, again

If I felt like I couldn’t quite make the “embedded storyteller” thing work for the people who’d conferred the title on me, it did have a galvanising effect on the time I spent outside of the studio: it made me start to tell a different story, one of my own, a true and human story with some ups and downs.

Truth is that this job at Made by Many was the first work I did after coming back from a breakdown in 2014, while I was living and working in Berlin – what’s technically known as a “major depressive episode”. I spent a year out recovering, and when I started at Made by Many I was relieved to discover that it’s a company which takes these problems seriously, and understands that people can be fragile and eccentric.

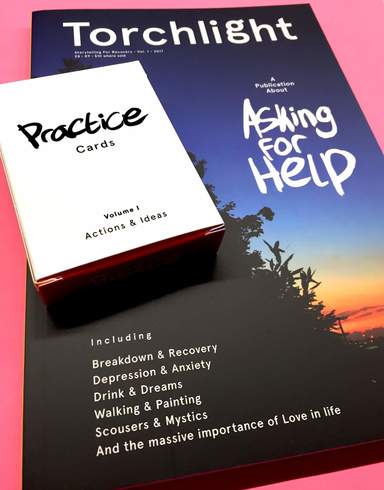

The story I wrote turned into a printed object, something that’s a bit like a book and a bit like a magazine, which is entitled “Torchlight: A Publication About Asking for help”. It tells the story of this breakdown and the subsequent recovery, and talks honestly about my experiences of anxiety and depression. It comes with a pack of “Practice Cards” which show helpful suggestions on living with these conditions: shuffle the pack, pick two and try to do one every day. Practice Cards are a way to make a game out of getting better.

n the spirit of the Thursday night campfire moment above, I’ve been presenting the Torchlight project (tagline: Storytelling For Recovery) in a series of low-key, salon-style storytelling meetings, in Berlin and London, and I’m planning to do more because it seems to me that this area – the field of human vulnerability and expression – is where storytelling can really mean something.

Telling stories helps both the teller and the listener.

As I said at the top, storytelling can mean different things to different people, at different times and in different contexts, but I hope in this story I’ve explained what it means here at Made by Many and in my own life, where these days that “storyteller” title feels a bit more comfortable.

Thanks for listening.

Continue reading

The portfolio you send is not the one you present

How to make your design portfolio work for you

Redefining the employee experience

At Made by Many, we’ve been building digital products and services for consumers for over a decade. However, rarely have we had the opportunity to create ...