In previous posts we’ve described the background of our expedition into Telehealth, in particular the business implications. In this post I’ll talk about what else we at Made by Many could uniquely add here, given our expertise in human-centred design and technology. How might we make a positive difference to the lives of people affected by diabetes using design and technology?

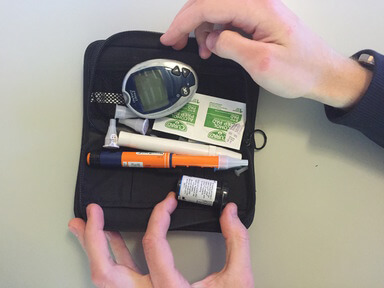

Reason being, over the past few weeks we have been designing something quite special — a new service that helps people affected by diabetes to stay on top of the condition day-to-day, as well as make positive improvements to their health in the long term. From proactive blood-glucose management through to emotional and motivational support, our service will foster a care network made up of patients, family, friends, guardians and medical staff.

After iteratively designing and testing prototypes with over 20 patients, carers and medical professionals over two weeks, we have begun building an app that will serve as a precursor to a broader Telehealth service. Before I reveal more, I’d like to share what we discovered along the way and how that makes our app a little bit different.

Listening to the experience of people affected by Diabetes

Before making any prototypes, our small team spent one week talking with people who have Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes and their carers. We immediately found that the condition has a far-reaching effect on people's daily lives that extends to family members, friends and even school teachers.

Here are some of the key insights

When speaking with children who have Type 1 Diabetes and their parents, we found that child guardians often act as surrogate patients — supporting and caring for the child 24/7. It is common for a mother to wake up in the middle of the night to check that their child’s blood sugars are not too low — if they were, they would wake the child and feed them something sugary like Coca-Cola.

Children with Type 1 can be so well supported by their parents that they are able to live relatively normal lives. In many cases measuring blood-sugar levels by pricking fingers and injecting insulin becomes normal for a child. One young boy we spoke to was more concerned about how often he had to text message his mother to allay concerns about his current condition. Texting mum or dad at school can be embarrassing for some kids.

In the case of young children, school can be a nerve wracking experience for both children and their parents. The child requires a teacher at school who is trained in basic diabetes care in order to check the child is caring for themselves properly. But between, say, 34 other pupils and one with diabetes, it can be a challenge for the teacher to stay up to date with blood glucose readings.

When we spoke to adults with Type 2 diabetes we learned that the condition goes far beyond physiological need. People depend on their nurse for emotional support too. Perhaps the biggest surprise to us on this project was the prevalence of depression and mental illness in people who have diabetes. It can be difficult for Type 2 patients to take medication or stick to a diet when they are feeling emotionally low. With intermittent medical support from the NHS, many people do not get the emotional support they need.

There was another need that we heard from all people with diabetes that we spoke to. NHS appointments are dreadfully tight for time, limiting care to appointments every three months that only last for 15 minutes to half an hour. This is not enough time to talk to a nurse about anything other than their blood glucose readings, meaning that patients do not feel like they get to discuss how the condition affects their life at home, at work and in their relationships with loved ones.

Talking with medical professionals

Meanwhile, we spoke to a range of medical professionals from a senior Diabetologist to GPs and diabetes specialist nurses. We were amazed to learn how nurses in particular go above and beyond the limitations of the NHS to deliver care that will have a lasting impact on the long term condition of a person with Diabetes.

Our team repeatedly heard that nurses see their role as lifestyle coaches and motivational support for people with diabetes. They can only find time in very short appointments to measure a patient’s blood and go over their recent medical history, and then go beyond the call of duty to talk with patients by phone and email.

This allows the nurses time to assess the patient’s lifestyle choices and encourage them not to fall back into bad habits such as failing to take their medication, eating poorly and not exercising. Unfortunately however, we heard that the NHS does not recognise this extra time, and so many nurses are not being incentivised to give the care that their patients need and they risk burning out.

Nurses talked at length about the close relationships they’ve built with some of their patients – relationships which can be almost telepathic. One nurse we spoke to made a casual joke to a patient on the phone, but knew from his response that the patient’s blood sugars were dangerously low. Relationships like that can save lives.

We also heard from Nurses and GPs that patients with diabetes are asked to record their blood glucose readings by hand in a notebook. This is because digital systems do not integrate between clinics in the NHS, and patients need to carry this data themselves. This is also a problem because diabetic patients are prone to misrepresenting their results, which many of our participants also admitted was true.

So how might we…

Our team spent a few days connecting the dots between these different conversations, uncovering a number of opportunities for design and technology to augment the experience of diabetes care.

In order to turn insight into action, we articulated these as ‘how might we…’ statements that act as specific design challenges for the next step in our design process — making prototypes.

(by the way, we refer to people with diabetes as ‘patients’ whenever we speak about them in the context of care from a nurse or other medical professional.)

Family members and peers are effective at motivating people with diabetes to manage their condition better. How might we enable family members to see the current state and the incline/decline of the patient’s condition?

People with good support networks have a more positive attitude about their diabetes condition. How might we help people without support networks identify with their own emotional needs?

Parents are overwhelmed by their responsibility to care for their child are constantly worrying and find it difficult to find free time. How might we alleviate some of the burden from parents so that they can find more free time and respite?

Patients need regular contact with medical staff who they know, trust and get on with. How might we make both patients and nurses feel personally connected with remote communication?

Nurses go above and beyond the call of duty to give lifestyle advice to their patients, meanwhile patients feel that their personal needs are not being met. How might we speed up physiological checks so that conversations can be more directed towards lifestyle?

Nurses prefer patients who proactively self-manage and share information. How might we encourage and remind patients to record their data (blood-glucose, carbohydrate consumption, exercise, emotional state) without adding extra burden to their lives?

So, there is a lot we could pack into a service with potentially life-changing capabilities. In the next post I’ll share how we took these opportunity statements forward into a week of making and how this helped us learn enough to begin building an app that we can put in the hands of real people. Check back here very soon...

Additional writing and editing: Sam Small