On empathy in design research

We talk about empathy all the time at Made by Many in terms of design research and making things. But the design-technology-business sphere we operate in has regurgitated this word so many times to the point of rendering it utterly meaningless. Is the way we talk about empathy in society, but also in design research broken? And could ‘designing with empathy’ perhaps lead to misguided design decisions?

I'm not only pointing fingers at you, I’m guilty of this too. I walk into my local organic café to buy a lunch of tofu, kale and chia seeds in a biodegradable box for a bazillion £££s and then pretend to ignore the Big Issue man outside who knows exactly what I just did. Call it lack of empathy, call it #middleclassguilt, either way something is wrong here.

Despite its Ancient Greek linguistic roots, the concept of empathy saw its first surge in the 19th and 20th centuries, after which behavioural psychologists and neuroscientists have added even more nuance to its definition today. To most of us though, it's about being able to put ourselves in each other's shoes. I can still hear my mother on the crackling phone line telling me that I don't have enough of it. Neither of us do, I concluded.

Do you practice what you preach?

So you already know that I eat tofu and kale. You shouldn’t be too surprised that I want to tell you about the Buddhist meditation practice, metta bhavana. A while ago my boyfriend and I were walking to work, chatting about the meaning of life and what to have for dinner. The subject turned to a meditation exercise that he was practising called metta bhavana.

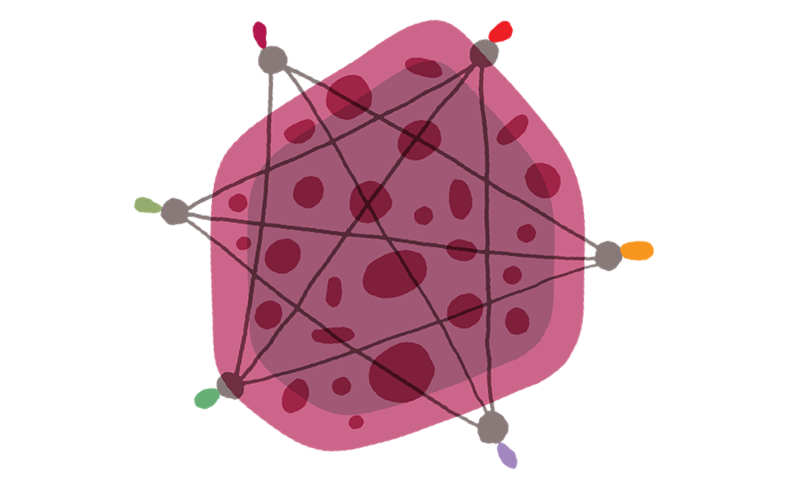

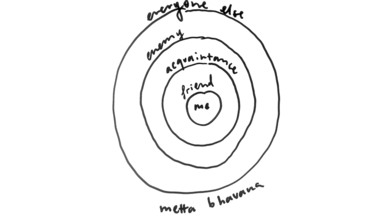

Metta is the feeling of ‘non-romantic love, friendliness, kindness’, whereas bhavana is understood as ‘the cultivation of this feeling’ - ‘loving-kindness’ in short. It’s an emotion that you build up in five stages: feeling metta for yourself, for a good friend, a neutral acquaintance, someone you dislike, and in the final stage, you think of all four people together and extend those feelings to everyone around you. I see it as a concentric circle diagram, which rests on the core of you feeling loving-kindness for yourself. Without acceptance and empathy for yourself, you cannot achieve loving-kindness toward others. And so metta bhavana is by far an exercise in humility.

It’s a feeling that has been expressed by the great religious and non-religious thinkers of our times. It’s easier said than done, but it’s something to strive towards. The more I think about it, the more it rings true in my work too. The more attentive I am to my needs as a human being, the more I will be towards the people I interact with during user interviews, as well as my colleagues. Do not mistake this for putting yourself before others, just remember to check in with yourself to see if everything is OK before you tackle your work. Empathy is not a switch you can turn on and off during a focus group, whilst adjusting gradients in Keynote or writing lines of code in Ruby. No one said this would be easy.

Does empathy always imply helping others?

In her recently published collection of essays, author Leslie Jamison discusses our self-perception when we feel empathy. Often we feel ‘a little bit dirty or polluted’ because feeling empathy often comes with feeling pride. Is this allowed?, we ask ourselves, bewildered by human complexity. A good example of this is people posting what seem to be trivial expressions of empathy on Twitter when natural disasters strike, boiling the blood of those who deem this simply crass. Even writing a piece about empathy has its dangers of being perceived as lofty and patronising.

Jamison goes on to say that we are compelled to commit altruistic actions to extend our feelings of empathy. Altruism as a consequence of empathy legitimises our inclination to design and make things that are helpful to people. But that’s a potentially slippery slope that leads to inflated egos. Is empathy also the ability to take a step back and say that actually there is no product or service to design for now? Do we need to help lay the foundations for change before we go in and disrupt with a new product? Furthermore, in the world of client relationships, big budgets and deadlines, can empathy and altruism truly be felt by teams when time and money are precious?

What are the limits of empathy?

‘The problem comes when we try to turn feeling into action’, says NY Times journalist David Brooks when discussing the limits of empathy. He goes on to criticise our obsession with empathy as a shortcut to feeling progress without actually stopping to think about its implications. Is empathy only a positive force when we do not act upon it? Is it too easily crushed by self-concern? And is designing and making things with empathy basically a contradiction since it puts you in the picture too? ’We’re often at our best when we’re smart enough not to rely on it,’ concludes Paul Bloom.

Having discussed this with others, and bearing these constraints in mind, I still think we can use empathy in design but it must be coupled with humility. As I already mentioned, the danger of designing with empathy is that it can often lead to inflated egos. Being aware of this weakness, and counteracting with a good dose of humility can help prevent this. Seung Chan Lim talks about humility in his creative process, which allows him to admit that he does not know, but gives him enough confidence to not let anyone convince him that he’s crazy.

By placing the users at the centre of your work, accepting often unexpected feedbackfrom them and building platforms that enable change (as opposed to enforcing change), big egos naturally deflate. We’ve talked about how this can be done throughout projects that we run at Made by Many. As a design researcher, I see it as my responsibility to perpetuate empathy for those who we are designing for. This can be achieved through regular activities that involve face-to-face contact with the user, the design team and client, daily research updates during morning stand-ups and analysing user-generated data and responding to it accordingly.

I am a strong advocate for face-to-face contact over any other kind when conducting user research, it allows for those spontaneous interactions that help us form an empathetic bond sooner, something that technology still largely denies us. From a practical perspective, this obviously adds more complexity to project planning, with extra travel arrangements being made to bring users and researchers together, spending extra time locating the right spaces for interviews and negotiating deadlines and budgets in order to accommodate for this standard of research. However, if we see our research as a foundation on which we build a sound product or service, can we really afford to not go the extra mile when we conduct it? Failing to bring the user to the forefront renders designing with empathy futile.

Realistically speaking, the limits of empathy are also determined by the constraints imposed on us by clients in relation to project approach and implementation, cost structure or internal politics. We’ll always have to deal with this, so what are the strategies that will allow us to cope with these constraints without extinguishing the empathy we strive for alongside Made by Many’s make-test-learn approach? Before taking on a project, we warn our clients that this won’t be an easy ride. They will be involved in kick-off workshops that focus on the user and dismantle any assumptions they may have had beforehand. Further along a project timeline, there is no excuse for not involving a key stakeholder in user interviews, asking them to take notes and ask questions. As soon as the client can form an empathetic bond with the people they are serving, the easier it becomes for you to push for the standard of user research that you wish to conduct.

How can we become better at practising empathy?

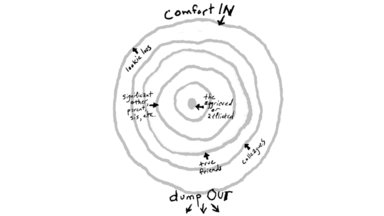

By now, I’ve realised that cultivating empathy is something that I’m going to have to work on for the rest of my life. No biggie. Something that has helps me with this daunting task is The Kvetching Order by Susan Silk and Barry Goldman in their article 'How Not to Say the Wrong Thing' in the LA Times this spring. At the centre of the order is the person affected by a problem, the circles around that person represent the various people related to her - from close family members to distant co-workers. The person in the centre can say anything she wants about her problem to anyone, anywhere. The rule that applies to the rest is ‘comfort in’, ‘dump out’.

In practice this means you don’t offer expressions of ‘wise advice’ and ‘compassion based on your personal experiences’ to people closer than you to the centre of the circle. You express comfort in the form of readiness to be present and support. If you still have the urge to whine about how this problem of your acquaintance’s is bothering you, go and complain to an unrelated colleague over a cup of tea. Simply dump out.

It’s solid advice that you can apply in many settings. But when you’re tasked to interview a group of users about their sometimes sensitive experiences, needs and behaviours to better understand the issue you are designing for, how do you move past the compassionate presence that you are advised to maintain by Silk and Goldman and ask penetrating, yet empathetic questions of your interviewees?

Where do we go from here?

Designing with empathy is more complicated than a lot of people have made it out to be. And I still am not sure whether empathy is the right word we should be using here. Perhaps compassion or kindness are better fits, or perhaps designing with empathy and humility is the new path we should be taking.

Without getting too distracted by word choices though, it’s evident that designing with empathy extends further than our work, it is a conscious decision that should be felt in all areas of life, towards oneself and one another. And finally, it’s really the decisions you make after conducting empathetic research that should be weighed up most.

What are the motives behind your intended actions? How do these interplay with your business objectives, clients’ business objectives and client relationships? Are there ways of supporting users by giving them the means to help themselves rather than helping them out of self-concern or to relieve guilt?

That’s some food for thought for you there. I’m off to go eat some kale.

Continue reading

Can a few well chosen words improve inclusivity?

Yahoo, Facebook, Google and LinkedIn have all recently published diversity reports that reveal workforces that are overwhelmingly male, white and Asian.

...

Behind the scenes: how we helped Contagious nearly double YOY sales

Last year we worked with Contagious Communications to re-imagine and re-design their online business – a project that culminated in the launch of their co...

Could coding in the curriculum improve the tech industry's gender problem?

With the start of the coming school year kids in the UK from age 5 and up will have coding as a standard part of the curriculum. For the tech industry thi...